Feature

The mystery of Bach’s “unicorn”

Anneke Scott introduces the mysterious ‘corno da tirarsi’

Share this

FIRST PUBLISHED 28 DEC 2023

A good mystery always intrigues - and when the mystery is set for us by none other than Johann Sebastian Bach, who can resist? Certainly not Baroque horn expert Anneke Scott, and especially when the mystery revolves around Bach’s scoring for a “corno da tirarsi”. Continuo Connect caught up with Anneke to hear more about this “unicorn” of instruments.

Let’s begin, though, with a wake-up call from Anneke and, on the organ, Benedict Preece:

One of the fascinating things about Bach, Anneke says, is that many of his brass parts have been thought impossible to play. For example, in the second Brandenburg concerto, the brass parts are extremely high and in some early recordings you can hear a soprano or alto saxophone instead of a trumpet. And sometimes, in three of his cantatas (BWV 46, 162 and 67, all written in Leipzig), Bach specified a “corno da tirarsi'' to play in the orchestra - a mystery, because there is no such instrument known to us today. The music is very high - too high, really, for a standard horn of the time, and nothing like the explicitly-specified horns of the first Brandenburg concerto.

The name “corno da tirarsi” implies a horn with a slide (tirarsi, i.e., like a trombone). But that’s extremely odd: whereas trumpets and trombones are cylindrical, the horn is a conical instrument - and it’s not possible to attach a slide to a cone, especially not one coiled in circles. It’s also odd that only one corno da tirarsi is called for by Bach: horns normally come in pairs.

For years - centuries, even - we have not had any clear idea what Bach intended, but now Anneke has one: her very own corno da tirarsi, made for her by the Swiss maker Egger in 2016, drawing on the doctoral research of Olivier Picon. At last, she says, she can play in Bach’s cantatas on something that - perhaps - is close to what the composer intended.

It’s worth delving into the history of horns to understand the essence of this mystery, and the elegance of Anneke’s solution.

Anneke is a historical horn player, and as such, has to constantly swap instruments between pieces, because the horn changed significantly over the course of the history of classical music. Other instruments have too (steel core strings replacing gut strings, for example), but wind instruments in particular underwent radical changes in their design. As a result, Anneke has a large collection of horns (thoroughly explored on her prolific YouTube channel), requiring a completely different instrument, for example, for Bruckner, Berlioz, Brahms, Beethoven, and of course Bach.

Even within each composer’s lifetime, the horn changed - for example, Berlioz, on returning from a trip to Germany where he saw the latest in horn valve design, immediately re-orchestrated many of his most famous pieces. Wagner, in a move that’s anathema to the purist, re-orchestrated Beethoven’s symphonies, claiming that Beethoven “didn’t have the orchestra he deserved”! Bach, too, rethought some of his orchestration over time (possibly when the lone player of the mysterious corno da tirarsi had passed away…), and it’s only since as recently as the 1950s that we have had a single, standardised horn capable of playing all of the music from the preceding 250 years.

Originally, horns were fixed in length and therefore in the range of playable pitches, and the player would select a horn that was tuned to the tonic (or key-note) of the piece to be performed. As a result, horns were heard in the music at moments where the music “returns home” to the tonic key (this is also familiar with timpani, which were similarly fixed in pitch to the tonic and dominant notes of the music’s key).

Horns developed through the 18th century to allow for changes in key as music became ever more adventurous; players could change a horn’s tuning by the addition and removal of lengths of tubing called “crooks”. In the 19th century and today, combinations of valves operated by the fingers are used to add and remove these lengths instantly, but originally it was a time-consuming process.

Anneke recalls the horn parts in Beethoven’s 3rd symphony (the “Eroica”). In his time, it would have taken several minutes for crooks to be swapped, and the 1st horn changes from E flat to F in order to play the famous horn motif of the first movement. Beethoven then gives a lengthy rest to the player in order to change crooks for the next entry - but, Anneke says, the music there “could really use horns!” Perhaps Wagner was onto something, after all?

For audiences of Beethoven’s time, changing keys to suit the changing music would have been “like witchcraft”, Anneke claims:

“For me Eroica is such a blast because Beethoven really understands our role, very cleverly, he understands structure and pushes against it and breaks it down; he does the same with the role of the horn. It’s very radical. Our roles and symbolism, it’s very daring, playing with the audience’s expectations - it’s so much fun to play!”

The symbolism of the horn that Anneke refers to is a unique aspect of the instrument. The horn has, since time immemorial, been associated with the tradition of the hunt, and made its way from an instrument played on horseback to the music-making and organised revelry that took place afterwards. The hunting horn’s appearance in music was popularised among the aristocracy at ever-more-elaborate hunting lodges and country palaces, notably at Versailles, leading to the term “French” horn, and from there the fashion for including horns in formal music spread across Europe.

The hunt, being a favourite activity of the wealthy gentleman, was associated with honour and prestige. Moreover, hunting was dangerous and required customs and rules to be safely observed; therefore, you were a Person of Quality and a Person of Standing if you were involved in the hunt. So, in the sonic world, the horn became a symbol of honour and virtue, of being an upstanding person, of abiding by rules. In opera particularly, horns were used to suggest “the outdoors” via the link to hunting; musically, motifs of repeated fifths are often found (as in Bach’s “Hunting Cantata” BWV 208). By contrast, trumpets became associated with the status of a king, or even of God (or gods, as applicable to the plot!)

Returning to Bach and his corno da tirarsi, then. The unusual writing is immediately apparent in the parts in his Leipzig cantatas - it looks very different to what Bach normally writes for horn.

Invariably, horns come as a pair, and almost always they are tuned in D, F, or G - rarely otherwise. Early horn writing is around the fundamentals of the harmonic series (which allows a brass player to play many notes with a fixed length of tubing: the lower notes are far apart, but become close together as they become higher). Bach often writes high in the harmonic series (for example the 1st horn part in the first Brandenburg concerto) because that’s where a composer can obtain a melody or a scale thanks to the notes of high in the harmonic series being sufficiently close together. Lower in pitch, the music will be triadic or in fifths (just as in hunting calls and fanfares) - because notes that are lower in the harmonic series are further apart.

However, Bach writes for just one corno di tirarsi, not a pair! It usually doubles the sopranos and violins, for example playing the cantus firmus chorale melodies. It’s very high by any usual “horn” standard; it would fit an unusual instrument in B flat or A alto - i.e. an instrument where the required notes fall into place at the top of its harmonic series. But in this music it’s far more chromatic than can normally be played on any standard horn, even at the top of the range. Moreover, Bach uses a minor tonality - and the harmonic series is inherently major, so playing high in minor keys is difficult if not impossible on an ordinary horn of the time. And while Bach calls for various types of horn in his other music - corno and corni di caccia - it’s impossible that the music in the three corno di tirarsi cantatas is intended for the same instrument as, say, the horn in the first Brandenburg concerto or the Mass in F.

The corno da tirarsi that Anneke has is only one possible solution, as the original instrument (and any associated technical drawings) is lost. Her instrument represents a kind of musical “experimental archaeology” and while hypothetical (there are other approaches, for example by Thomas Friedlaender), Anneke is confident that her instrument is eminently plausible:

“I’m not saying this is what Bach had, we can’t say that. But we can say that everything in the instrument is something that a Leipzig maker of the time would recognise, so there’s nothing ‘new’ in there. The more I’ve played these works, the more convinced I am that this instrument perfectly suits this writing.”

As a highly sought-after horn player, Anneke has to constantly juggle which horn she’s due to play in the next few weeks. She says that horn playing comes in two types - the sprint (“fast, high, quick!”), and the marathon (“operas - Wagner!”), and therefore that you have to do the right kind of training or practice in advance to be “fit” for the demands that will be placed on you by the music. Unfortunately, therefore, Anneke had little time to get to know her corno da tirarsi properly - that is, until the Covid pandemic in 2020…

With little to do by way of live performance, Anneke came up with an unusual project: ‘Corno not Corona’. She had the idea of recording a new video every day with the corno da tirarsi, to work her way through Bach’s hundreds of chorales. She made no fewer than 191 videos (still available to watch on her YouTube channel), and says that she learned a huge amount as a result.

“It was a very good reminder of the learning process. One of the joys of being a musician is learning new things - pushing against things that you think are established truths. And I was trying to learn this hypothetical instrument - am I going to transpose? Read in concert pitch?”

There was a further benefit beyond becoming an expert at the corno da tirarsi. Horn players are often divided into “high” or “low” players (with a high and low player forming the usual pairing of horns). Anneke was typically a “high” player, but says that after 191 days playing this tiny corno da tirarsi her high range was enormously increased and strengthened, which, she says, is “just what you really need for the cantatas”!

Anneke Scott performed on the corno da tirarsi with Internationale Bachakademie Stuttgart in their “VISION.BACH” project in the Leipzig cantatas BWV 46, 162 and 67 in 2023, and continues to seize every opportunity to employ the instrument.

Anneke can also be found performing regularly with her group Boxwood & Brass.

Share this

Keep reading

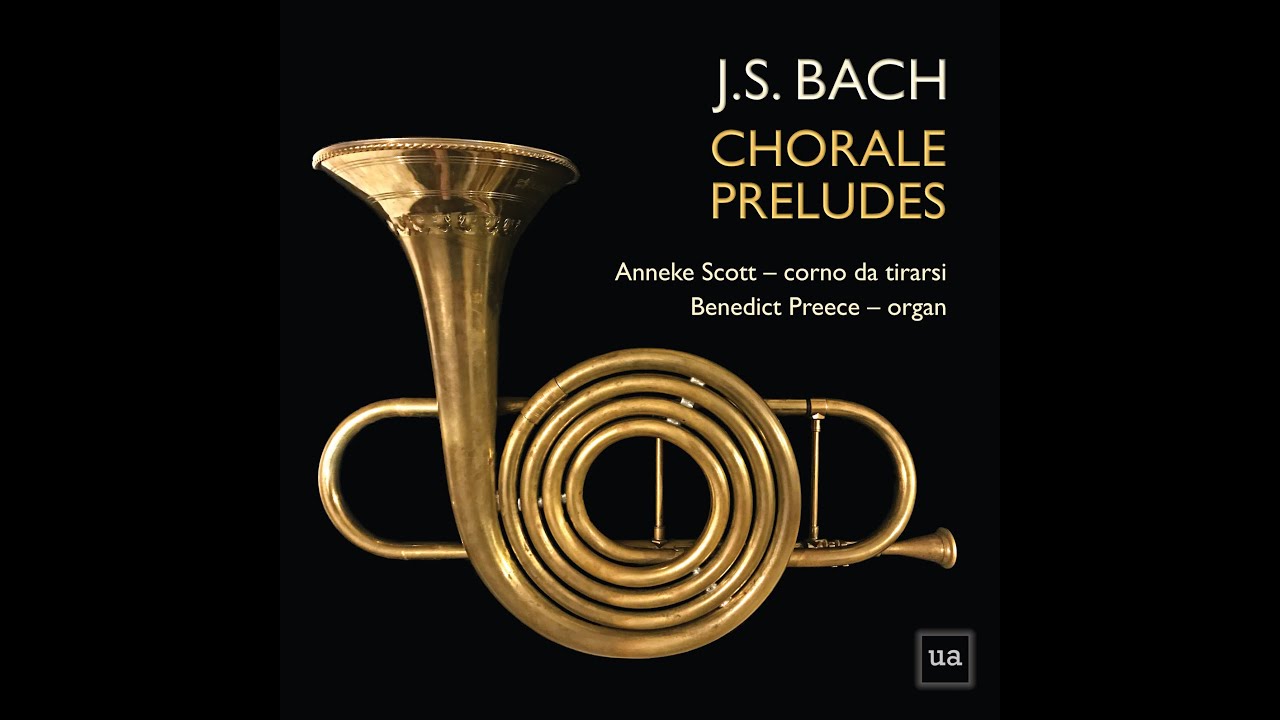

Sisters of polyphony

Laurie Stras uncovers the stories behind the extraordinary Biffoli–Sostegni manuscript, and traces the lives of the nuns who sang from it.

The Faerie Round: Music from the time of Elizabeth I

PIVA – The Renaissance Collective’s third album features dance and ballad music from late Elizabethan England.

Nardus Williams & Elizabeth Kenny: The Four Humours | Wigmore Hall

The celebrated duo dive headlong into the world of the Four Humours, physical properties believed to govern human behaviour from ancient times until the 1850s.