Feature

Angell’s Musick in Mortall’s Dresse

The story behind Galliarda’s programme based on the work of John Wilson of Faversham

Share this

FIRST PUBLISHED 30 JUN 2024

John Wilson, a prominent baroque composer, rose from humble beginnings to significant fame. Matthew Spring of ensemble Galliarda explores his enduring legacy.

Last year my brother moved to Faversham in Kent, in part for its convenience, but also because it narrowly escaped the town planners of the 1960s who wished to clear away its many historical buildings to make more room for the motor car; hence the town retains its old buildings. Visiting Faversham reminded me that John Wilson had been born there, and so I set off to see if there was a plaque commemorating his birthplace at the corner of Church Street and Abbey Street. A short walk to the town centre proved that there was, and what was more, he was included as worthy of mention in most of the church and town guides that I picked up. Although undoubtedly famous in his lifetime as one of the foremost performers and composers of song of the early English baroque period, he is little known today and his songs are seldom heard. Fortunately, the Continuo Foundation awarded Galliarda a grant that allowed us to increase the group in size, and to give a series of concerts and make a recording and video of Wilson's music.

Over the years I have worked on Wilson’s music, producing an edition of his 30 preludes in all keys in 1997, and more recently, a working edition of his Cheerfull Ayres or Ballads (1659-60) for the Lute Society. Researching his life in some detail I have come to the realisation that he was an exceptional survivor who had an extraordinary life – rising from very humble origins to being buried in Westminster Abbey with (for a musician) considerable honour. As his working life was so long and varied there were few leading musicians or poets of his time that did not know or work with Wilson. He was one of the most famous and prominent musicians and singers of the Stuart age; a man who was well known and well liked in the theatre, court, and the chapel royal.

After his early years in Faversham, Wilson worked his way into the city and the theatre, and was composing for masques by 1614: his comic setting of ‘Kawasha comes in majestee’, composed for The Masque of Flowers, was published in that year along with the text of the masque. This setting seems to have given him some early success and notoriety as a composer, though still only nineteen. As a boy he is likely to have been the ‘John Wilson’ who, in February 1608, was apprenticed for eight years to the actor John Heminges, a freeman of the Grocers’ Company. As early as the 1840s the musical antiquarian, Edward Rimbault, produced a pamphlet titled Who was “Jack Wilson” the Singer of Shakespeare’s Stage? suggesting that Wilson was the boy singer (Jack Wilson) mentioned in Shakespeare’s First Folio edition of Much Ado About Nothing (1623). This claim has always attracted a good deal of scepticism, but I found that Wilson did occasionally refer to himself as ‘Jack Wilson’ in later life. Evidence of the continued use of the colloquial ‘Jack’ in place of ‘John’ is found in a long masque-like piece by Wilson titled ‘The Wake’, which is the second piece in the first section of GB-Ob, MS Mus. d.238, p. 11, and GB-En, MS Dc.1.69, f. 8v. The Oxford manuscript contains the second treble and instrumental bassus, and the last line of the piece runs ‘which sings not the praise, and gives up the Rayes to Doctor Jack Wilson’. On f. 8v of the Edinburgh MS (with first treble and another instrumental bassus) we find the lines, ‘Twas meerly out of zeale to Dr. Jack’. This to me suggests that Wilson was indeed Shakespeare’s singing boy.

By around 1615 Wilson was attached to the King’s Men company, where he would have worked alongside Robert Johnson, taking over from him as composer and musician for the troupe from 1617. In particular, Wilson provided music for a string of plays by John Fletcher, though it is for the few songs with words by Shakespeare that he is probably best known.

Wilson’s compositions survive quite well as he was careful to collect them up during the years that he was in Oxford and had over 200 of them copied by his friend Edward Lowe, composer, copyist and organist of Christ Church, into a large presentation manuscript (GB -Ob, Mus MS b. 1) that he gave to the Bodleian Library when he became professor of music in 1656; stipulating that it should not be consulted until after his death. It is this manuscript that has the lute preludes and tablature accompaniments to over 40 of his songs. More than this he then put together 69 of his songs for publication in Oxford in three books. Cheerfull Ayres or Ballads was the first substantial attempt at music publishing in the city. He said that they can be used in different ways depending on the company available – as solo songs with instrumental accompaniment, or as two or three-part songs with or without accompaniment.

Wilson pointed out that these songs already existed as solo songs but that he had added other lines to increase the possibilities for participation and performance. The songs in Cheerfull Ayres represent and ‘showcase’ Wilson’s long career and his strong association with the stage and with masques. Along with Wilson’s own songs, the books include a handful of songs by composers close to Wilson – Robert Johnson, Nicolas Lanier and Thomas Campion – yet in each case they have been arranged by Wilson. Few of the ayres are heard today – partly as a result of Wilson’s sometimes idiosyncratic style but also because the printers were completely new to music printing and made many errors.

In celebration of the 350th anniversary of John Wilson’s death, I devised the concert programme for Galliarda to bring together a selection of Wilson’s works alongside those of a few of his many friends and colleagues: Tobias Hume, John Jenkins, Nicholas Lanier, and Henry and William Lawes. I wished to show that the songs from Cheerfull Ayres could be performed in different ways, so we increased the group to include 3 additional young singers – giving the programme the option of having some of the songs performed with voices alone, as solo songs and as ensemble pieces for everyone. I also aimed for variety by including songs with all the complicated ornamentation and vocal divisions, as found in some manuscripts, as well as a good deal of instrumental music by Jenkins (another Kent composer and a friend) and masque pieces from masques that Wilson had been in. As so many of the songs related to plays, we included some of the dramatic text that leads into the song to add dramatic context and had the singers memorise some of the songs. The title of the programme (Angel’s Musick in Mortall’s dresse) is taken from one of the eight commendatory poems that preface Cheerfull Ayres.

Wilson also wrote quasi-religious works in his Psalterium Carolinum (1657), that set words rendered into verse by Thomas Stanley from the Eikon Basilike, which was said to be the ‘devotions of his Sacred Majestie in his solitudes and sufferings’ before King Charles’ execution. This book was ready for sale on the day of the King’s execution and went on to be hugely popular and went through many editions. Wilson was a staunch royalist and this, as well as his close connection with the dead king, may have helped him in his later years to get royal appointments at the Restoration. We also included a piece by Henry Lawes in memory of his brother William Lawes after his death at the Siege of Chester in 1643. Wilson also composed an elegy for the set and his closeness to the Lawes brothers was a continuing theme in Wilson’s life. Their lives constantly intersected.

On the trail of Wilson in Oxford in the 1640s and 50s, I spent a very enjoyable morning in Christ Church library getting out all the manuscripts containing Wilson’s music - which includes some sacred music composed for Charles I while he was living in the college (and the Queen in Merton College). Later I went to the Balliol archives as I knew that Wilson had some association with the college when made professor. I was delighted to find in the huge buttery ledgers row after row of ticks for the many meals at which he ate there. He seems to have had a very good appetite and though he did not live in the college he ate in the College Hall on a regular basis.

Perhaps the ‘cheerfull’ of the title was less an indication of the nature of the songs, many of which are settings of serious poetry on the subject of love and sadness, and more about Wilson’s desire to create a set of books of his songs that could be used convivially in different ways, ‘as shall be requisite for company that shall use them’. It may also be that Cheerfull Ayres, and the reprinting of Psalterium Carolinum in 1660, represented an attempt to draw the attention of the returning court and the new king to Wilson’s long and continued support of Charles I and his cause. If this was so, it was successful. Wilson’s appointment to the new Lutes and Voices and then to the Chapel Royal followed two years after publication. On his return to London, Wilson was presumably too old, and his music too out of date, for him to be called upon to do much actual service, so these appointments were effectively his pension.

Performances of 'Angell’s Musick in Mortall’s Dresse' featuring Galliarda, Lewis Spring, Catherine Chapman, Chris Murphy and the Chalemie Renaissance Wind Band were supported by a Continuo Foundation grant.

Author: Matthew Spring

Share this

Keep reading

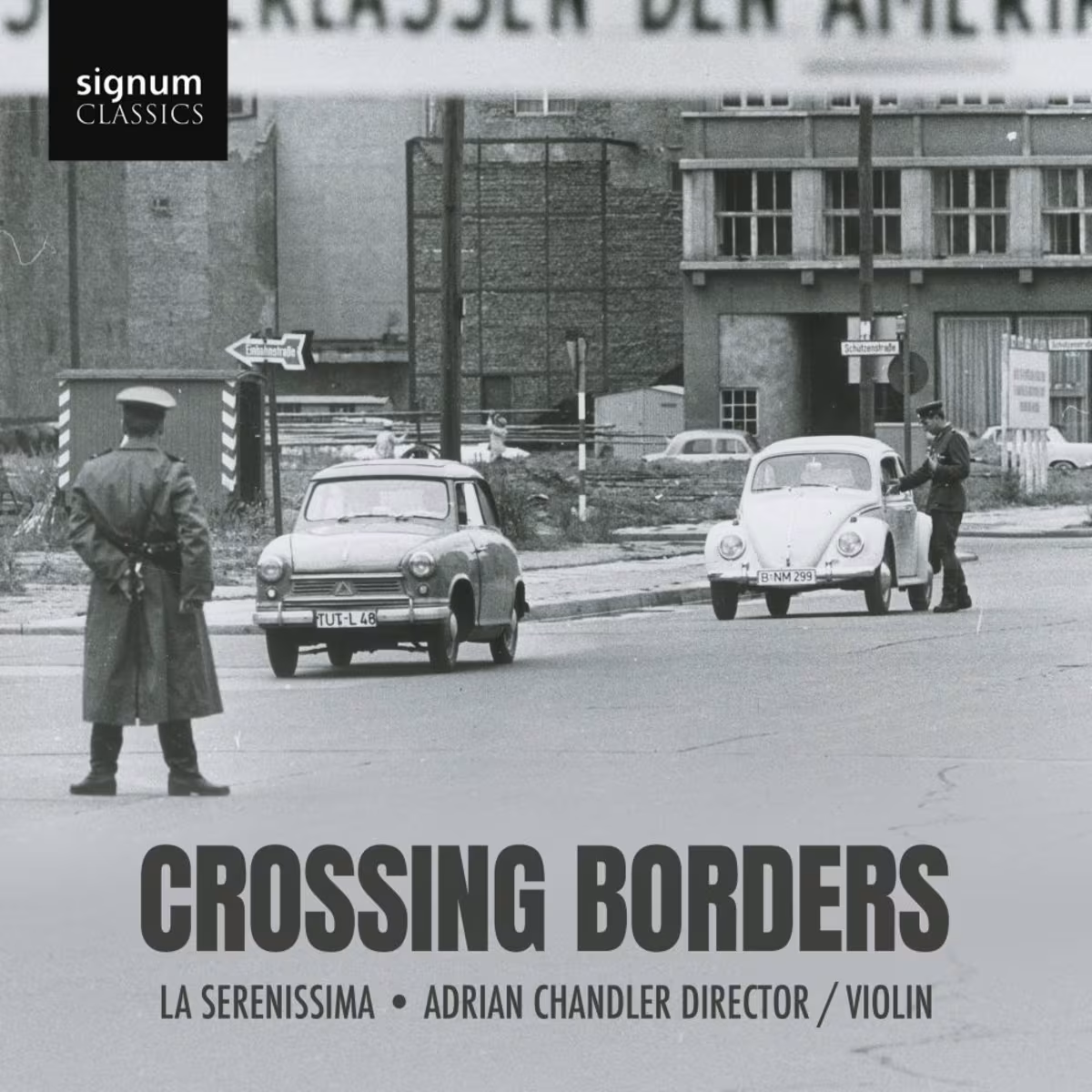

Crossing Borders

La Serenissima return with an album of works by Telemann, Sieber, Durante, and Brescianello – their 11th with Signum Records.

The Battle of the Organs

“Celestial Music did the Gods Inspire” brings to life the extraordinary story of the Battle of the Organs.

Peralada Easter Festival - A Report from a Catalan Stronghold

Continuo Connect’s Writer-in-Residence Simon Mundy shares his impressions from a recent visit to the Festival Castell de Peralada in Catalunya.